Settlement through Civil War

Jane Grey Swisshelm grew up in Pittsburg as the educated daughter of a family who fell into poverty after the War of 1812 and the death of her father. She came to Louisville as a bride in June 1838 with her husband who planned to go into business with his brother, Samuel. His business venture failed, but Jane had skills as a seamstress and lacemaker. She could earn the money that would keep them from being destitute; however, the culture of the time dictated that a woman's place was in the home. Her father and then husband were supposed to provide for her. As Jane stated in her memoirs, "To a white woman in Louisville, work was a dire disgrace."(Swisshelm 2004) So what could a woman do when the system failed: follow the cultural order and starve or risk social condemnation and take a job? In Jane's case, she managed to get a job with a dressmaker on the condition that the work be sent to and from Jane's home by a servant so that Jane would not be seen bringing work to the shop. Jane's memoirs detailed the difficult life of women in Louisville in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Women's contributions to labor were not well documented in the first century of Louisville's existence and a lot of information about the work women did then has been lost. For much of Louisville's early history, women did not belong in the public sphere. The societal norm was that women occupied a private sphere centered around the home. Newspapers rarely mentioned them. What can be found has been gleaned from census records, city directories, and the rare diaries of women's lives. The sparse information available provides a glimpse of women's lives in that time and shows that even while the societal norm was for women to occupy themselves with home life, sometimes circumstances demanded that they work outside the home to make a living. When they did, the first socially acceptable positions reflected their traditional roles in the home.

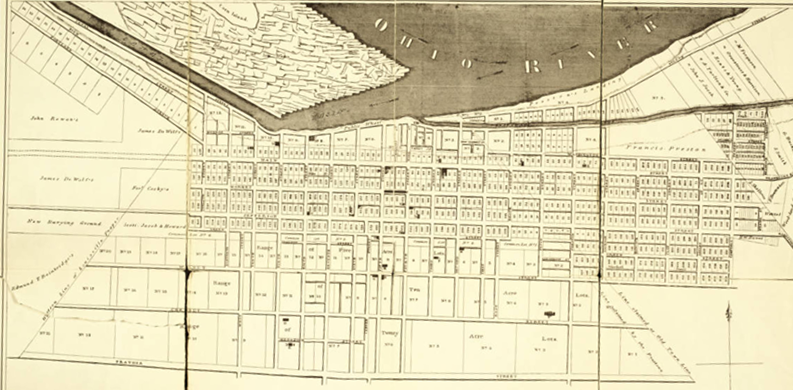

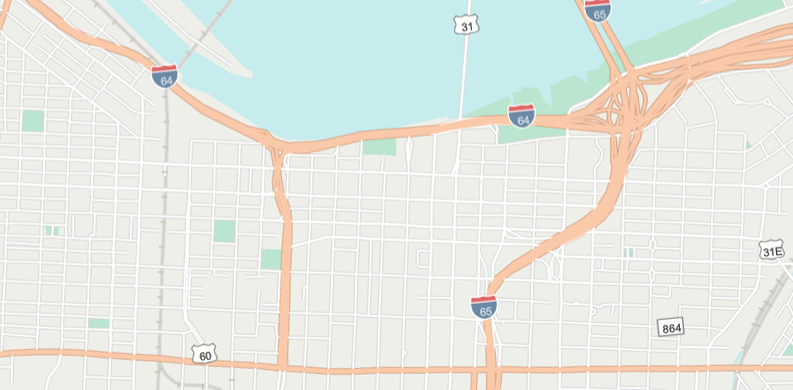

The 1832 map shows Prather Street (currently known as Broadway) as the southernmost street. Before: 1832 (Hobbs 1832). After: ESRI, 2020.

Pioneering women and the birth of a city

In Spring of 1778, George Rogers Clark led a group of families and a garrison of men along the Ohio River to create a settlement on what was later named Corn Island.(Yater 1979, p7) This settlement would become Louisville, Kentucky. That initial settlement revolved around the home and creating a sustainable life in the wilderness. Farming alone could not provide sustenance for the settlement so men hunted for game and did what planting and harvesting they could. The women's work was more consistently done at the home — spinning flax, weaving cloth and sewing linsey into clothing, as well as milking the cows and preparing the food.(Casseday 1970) Women were also responsible for taking care of the home, educating their children and tending to their family's health. When women did begin to work for pay (or barter), these traditional roles offered a route to employment. For example, an entry in a British officer's diary from March 1779 indicated a business transaction with a woman cook: "We procured some bread for our ensuing March, for the baking of which I was obliged to give the Lady Baker my quilts."(Yater 1979, p8)

By 1830, Louisville had over 10,000 people as well as churches, dozens of stores, a city school, and tobacco, cotton and wool factories. The city's first directory was compiled in 1832. Women's names appeared far less frequently in the directory than men's names as it only listed the heads of households. In addition to names and addresses, the directory provided the occupations of each head of household. Occupations listed for women included teachers, milliners, mantua (dress) makers, and boarding house operators.(Louisville 1832) All of these occupations echo the work women did in the home — teaching children, sewing, cooking, and maintaining the household. The directory listed Eliza Thompson as a "colored" washer. The fact that she is listed at all indicates that she was a free Black woman rather than a household slave. The documentation of her occupation as a washer is significant, both as a reflection of traditional household duties, but also as one of the first paying occupations available to Black women.

Maintaining Households

Of all the occupations for women, running a boarding house most clearly mirrored the work women did in the home. The boarding house keeper had many of the same responsibilities, including cleaning, cooking and tending to the comfort of the inhabitants. Boarding house work had the added benefit of providing income without actually leaving the home. Louisville's first directory showed running a boarding house to be a very popular occupation for women. In fact, the number of women running boarding houses outnumbered all other jobs for women combined in 1832.(Louisville 1832) Part of the reason for this was a shortage of housing at the time. Only 24 states had joined the United States. People were still flocking westward, particularly men. The census of 1830 showed that free men outnumbered free women by 4,951 to 2,975 in Louisville.(Census Office 1832) With this influx of unattached men came the need for more housing. Boarding houses answered this need and many of them were run by women. A number of boarding houses were located along Water Street near the Ohio River and convenient to rivermen and travelers. The 1832 directory indicated twenty-two women running boarding houses. Mary Baxter, for example, ran a boarding house at Fifth and Water Streets.(Louisville 1832) The work of a boarding house landlady frequently included interviewing potential boarders, collecting rents, and running the household. Caring for the sick in the household also fell to landlady. Cooking meals and cleaning may have been split between the landlady and any servants or slaves in the establishment.(Gamber 2005)

Women continued to have a strong presence in this field as evidenced by the census rolls and city directories prior to the Civil War and by census statistics after that. The 1870 census shows that women accounted for 62% of the boarding and lodging house keepers in Louisville.(Statistics 1872) By the turn of the century, women had taken over the occupation with 91% of all boarding house keepers in Louisville being women.(Special 1904)

Women were also strongly represented in the occupation of domestic service which used the skills they learned at home, but not in Louisville's earliest years. The 1832 directory does not list a single woman as a servant. The closest listing is one for Eliza Thompson, a "colored" washer.(Louisville 1832) Domestic work was largely handled by the city's 2400 slaves. By the next census there would be another 1,000 slaves with females outnumbering males by nearly 700 people.(State 1841) The changing demographics, especially those for female slaves, reflected a growth in the need for household labor, including cooks, laundresses, and cleaning help. Advertisements, such as these in the Louisville Daily Journal, indicated the types of jobs open to women:

Negro Woman Wanted. — A negro woman, a good cook and washer, wanted for a small family, for the present year. For one that can be well recommended a liberal hire will be given.(LDJ, Jan 14 1843)

Negro Woman for Sale. A likely and very valuable negro woman, with one child, for sale low for cash. She can be recommended as a first rate house-servant, cook, washer and ironer, nurse and seamstress.(LDJ, Jan 16 1843)

Some placements were aimed at very young women, such as this one, "Wanted to hire or purchase — A likely negro girl, 11 or 12 years of age."(LDJ, Mar 16 1843) The girl may have performed household chores along with caring for young children. Adult women would have been preferred for positions such as cooks and seamstresses which required particular skills developed through experience.

Among the advertisements in the city's 1855 directory was one from L. P. Crenshaw, Real Estate and General Agent looking to hire 300 servants. It is unclear if the ad means servants in the modern-day sense of paid laborers or if it was aimed at slave owners who wanted to hire out their slaves, but it does give perspective on the relative worth of the labor for particular jobs at the time:

Hiring Servants. — I am now hiring out yearly about 300 Servants of all ages and sexes. Boys and Girls from 8 to 12 years of age hire at from $30 to $50 per annum. Girls, suitable for Chamber-work, at from $75 to $100. Women, Cooks, Washers, etc., at from $100 to $125. Men, for ordinary work, at from $125 to $150; on Steamboats, as Firemen, etc., at from $35 to $45 per month. They are well fed and clothed and the Taxes and Doctor's bills paid by the hirer.(Louisville Directory 1855, p96)

With so many slaves available to do the work, there was less need for White women to take on domestic work in the early 1800s; however, by the 1860 census, the most common job for women in Louisville was that of domestic servant.(National Archives 1860)

Educating Children

The first city school was created in 1829, soon after the city was chartered. The mayor acted as superintendent and the city council chose six men as the trustees.(Casseday 1970, p179) Girls were taught separately from boys; Miss Catherine Ewell acted as principal of the Female Department. The curriculum for girls included arithmetic, geography, grammar, and history.(Louisville 1832)

Private schools provided educational opportunities as well. Sister Catherine Spalding established Presentation Academy which opened in 1831.(Doyle 2006, p96) The original school was located in the basement of St. Louis Church on Fifth Street between Green and Walnut Streets (now Liberty Street and Muhammad Ali Boulevard).(Abner 2001) The Sisters of Charity of Nazareth (located 35 miles from Louisville) sent Sister Catherine to Louisville to act as Sister Superior. In the first year, the Sisters taught fifty to sixty young women. While the school was a Catholic institution it also accepted non-Catholic students.(Doyle 2006, p97) The Sisters of Charity would be responsible for opening and administering more than twenty Catholic schools in the Louisville area in the following century.

In 1851, a new city charter provided for the creation of a public school in each ward. The Board of Trustees opened a female high school in 1852.(Yater 1979, p79) The city schools were open to those who were unable to pay the tuition of private schools. Initially, boys and girls were taught separately by male and female teachers, respectively. In the early 1850s the city employed 31 women and 25 men as teachers with salaries ranging from $250 to $700 per year.(Casseday 1970, p220)

Prior to 1860 the Census of the United States did not record occupations for women. The aggregate numbers for 1860 only indicate the total number of employees with no details on how many were male and how many were female; but, the actual forms used by the census takers indicate specific women working in education. In Louisville's fourth ward, for example, Josephina Masestadt was listed as "teacher of music," Charlotte Pearing as "private school teacher" and Sallie Clarke as "teacher city school."(National Archives 1860)

Tending the Sick and Needy

As the person most tied to the household, the woman of the house was available to stay with bedridden relatives in times of injury or illness. From settlement to 1823, the area had no hospital, and doctors visited the sick and injured in their homes usually for severe cases only. Women frequently tended to each other in childbirth with some becoming so experienced as to be recognized as midwives. The 1832 city directory lists Mrs. Leuba as an "accoucher," an early term for midwife.(Louisville 1832) Twenty years later, the city was large enough to require 23 midwives.(Casseday 1970)

In the early 1800s, people learned nursing skills hands-on. There were no schools or accreditation. Frequently, doctors had no formal training either. The Louisville Marine Hospital did not open until 1823 and the Louisville Medical Institute, the first medical school in Louisville, was not established until 1837.

The earliest known nurses in the area were the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth. In 1832, Louisville was devastated by cholera. Bouts of fever and cholera spread through the community in waves earning Louisville the epithet "Graveyard of the West." Mother Frances Gardiner, the supreme at the Nazareth motherhouse at the time, sent the first group of sisters to help with the sick in October 1832.(Nazareth 1972) Sisters Margaret Bamber, Martha Drury, Martina Beaven and Hilaria Bamber went from house to house taking care of the ill. They took the newly orphaned children they found back to Presentation Academy which was shut down for the duration of the epidemic. By the end of the plague, the Sisters had twenty-five orphans living with them and three Sisters had died from cholera. Sister Martha Drury contracted cholera while nursing the sick but recovered and continued to work where she was needed.

Caring for the sick and orphaned were integrally tied together at this time for the Sisters. Under the direction of Sister Catherine Spalding, the Sisters established an orphanage called St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum. It opened in 1834, but within two years they had taken in so many orphans that a larger space was needed. In 1836 the orphanage moved to Jefferson Street.(Doyle 2006) The Sisters set aside space in the new orphanage to act as an infirmary. In a letter to Sister Claudia Elliot, Sister Catherine expressed the magnitude of the work the Sisters of Charity had accomplished in a relatively short period in the areas education, nursing, and care of orphans:

The new addition to our house is filled with orphans. Remember when we moved to Louisville we were only 4 Sisters, to begin a poor day school – now see what has grown out of it. – In five years we got this place & separated — Now there is a large pay school & free school on 5th Street. – this asylum is full, & the Infirmary increasing that we might now divide this establishment & make two of it. – if we had room for it.(Spalding 1848)

In 1853, Sister Catherine got her wish. St. Aloysius' College, a former Jesuit property, was rented. Patients at the orphanage were transferred to the new location which was named St. Joseph's Infirmary.(McGill 1917, p111) By 1860, seven Sisters of Charity provided care for patients at St. Joseph's Infirmary.(National Achives 1860)

With the outbreak of the Civil War, more Sisters would find their way to makeshift hospitals in Louisville. Bishop M. J. Spalding and Brigadier General Robert Anderson would come to an agreement that the Sisters of Charity would "nurse the wounded under the direction of the army surgeons, without any intermediate authority or interference whatsoever."(Memorandum 1861) The Sisters reported for duty in November 1861 at three hospitals. They learned bandaging procedures from Sister Victoria Buckman, the Mistress of Novices. They cared for wounded soldiers from both sides, as well as the "lambs," little drummer boys who acted as mascots for the units.(Angels 1917) The conditions of battle and the time delay between injury and arrival at the hospitals meant that the nurses gained experience in dealing not only with wounds, but also with infection and contagious disease. A number of the Sister nurses died from illness contracted while tending the sick soldiers. Sister Catherine Malone, for instance, died at the hospital at Broadway and Ninth Street. A doctor from the U.S. Army Medical Division wrote his condolences to the motherhouse:

I regret very much to inform you of the death of Sister Catherine at General Hospital No. 1, in this city. She, as well as the other Sisters at the hospital have been untiring and most efficient in nursing the sick soldiers. The military authorities are under the greatest obligations to the Sisters of your order.(Account 1861-1863)

Besides the Sisters of Charity, a number of women worked as lay nurses during this time, including Eliza Sells and Bridget Monohan.(National Archives 1860) The census rolls show that they both worked as nurses and lived in Louisville's Fourth Ward. While the numbers of women working as nurses during this time is low compared to other occupations such as domestic service, nursing would later become a field heavily dominated by women. Along with education, nursing provided women with one of their first professional opportunities.

Running the family business

Just as women on the homefront took on jobs traditionally done by men when men were not around, so did women take on business responsibilities if there was no man to do it. Widowed women, in particular, were allowed to do things that single and married women could not, including taking over their husbands' trades. Anne Christian, for example, operated a salt lick operation in the 1780s. Major Erkuries Beatty, a paymaster for the Army, made note of the widow in his journal:

Came to Salt River to breakfast... Here we were informed of the excellency of [Bullitt's Lick] for making salt. It at present belongs to Mrs. Christian, widow to Col. Christian, who was killed by the Indians two or three years ago. She rents it to different people... for 12 bushels of salt each a week, which brings her in a year 3120, and that will sell in this country for two dollars a bushel in produce or about a dollar and half cash.(Yater 1979, p18)

Colonel William Christian died in 1786 and left "Saltsburg," as he called it, to his son John. Because John was still a minor, his mother, Annie, ran the salt lick with the assistance of a business agent.(McDowell 1956, p258) This was not unusual for the time. Women seldom owned property in their own right; however, widows might administer property and businesses left to them or the underage male heirs. In Annie's case, it appears that a male relative attempted to take over the running of the business after William's death. In 1788, Annie Christian petitioned to be appointed the guardian of Johnny and the salt operation:

"Saltsburg is Johnnys [sic] whole dependence I wish to carry on the works most conducive to his interest, & was surprised to hear you had leased them out for Seven years, a term I cannot agree to, I intend to rent them yearly until the debts are discharged, & we can carry down our own hands to work the place, & then a much more Saving plan must be fallen upon than the present one."(Bullitt, f394)

Some women had careers in crafts or businesses that were usually reserved for men because of their family ties. In 1860, for instance, Weillmena Lepening worked as a shoe binder. She was 26 years old at the time and living with two older brothers who worked as shoe makers.(National Archives 1860, p18) While most young women who worked at that time were taking positions as domestics, Weillmena performed a skilled craft and worked in the family trade.

Some other early businesswomen included Miss Mary Richards who ran a second-hand furniture store, Mrs. Antonia S. Melcher who owned a pottery factory, and Mrs. B. Rumble who ran a grocery. Around the Civil War, an increasing number of women owned groceries or other stores. While the assumption might be that the women took over these stores because no man in the family was available to take over, that was not always the case. Both Elizabeth Ziegenhien and Mary Chapman who ran groceries, had adult sons living with them yet the trade of grocery was listed with the women. The young men were employed elsewhere – as a shoemaker and painter's apprentice, in the case of Chapman's sons.(National Archives 1860)

Conclusion

The occupations of women in Louisville from the late 1700s through the Civil War grew out of their traditional roles in the home. As women began to hold jobs away from their own households, those jobs often resembled the work they did at home. Women became servants or boarding house keepers, teachers or nurses. With the exception of boarding house work, which started to decline in the early Twentieth century, women continue to be heavily represented in these occupations.